Hemp for CBD oil takes off in Oregon

Published 4:22 pm Friday, June 7, 2019

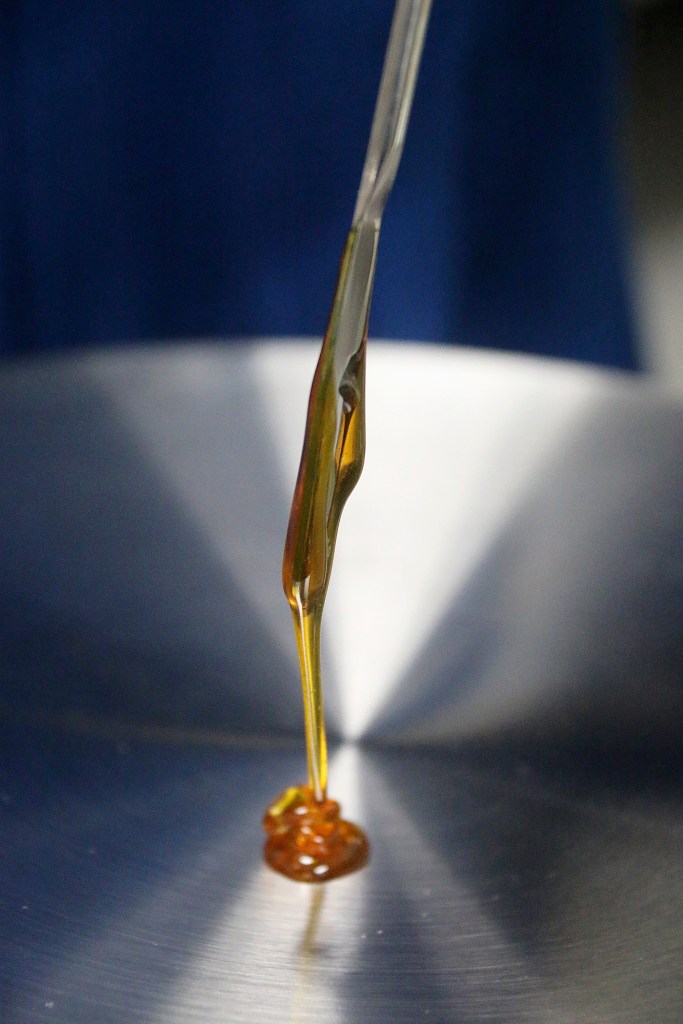

- CBD oil.

For a crop facing unprecedented uncertainties — agricultural, regulatory and economic — hemp is finding its legs remarkably fast in Oregon.

Growers have embraced the plant despite a continually shifting legal landscape and a relatively fledgling knowledge of the most effective cultivation practices.

“It’s an interesting puzzle because there is no road map and you have to figure it out on your own,” said Ken Iverson, who began growing hemp about three years ago near Woodburn.

More than 50,000 acres of hemp are expected to be planted in Oregon in 2019, up from 11,500 acres last year and 105 acres in 2015, when the state government began licensing the crop’s production. Oregon is now the second-largest hemp-producing state behind Kentucky.

“I don’t think anyone expected it to grow as much as it did or as quickly as it did,” said Sunny Summers, cannabis policy coordinator for the Oregon Department of Agriculture. “We didn’t think we’d see conventional agriculture adopt it as a rotation crop as quickly as we have.”

Farmers concerned about producing something that was until recently a federally-prohibited drug have a powerful incentive to overcome those qualms: Consumer demand for cannabidiol, or CBD, a plant chemical that’s touted for reducing pain and inflammation, among other health benefits.

The compound, which is extracted from hemp flowers, is being added to a multitude of products from fast food to cosmetics to pet food.

“It’s in everything,” Summers said.

While hemp has traditionally been grown for its fibrous stalks and oilseeds, Oregon’s farm industry has largely focused on CBD as the processing capacity for those other components still remains lacking.

“I know very few growers who are growing for anything but CBD oil,” said Gary McAninch, manager of ODA’s hemp program.

Oregon’s status as a leader in CBD-specific hemp is partly the result of its history with illicit cultivation of marijuana, which is also a cannabis plant but has mind-altering effects.

Marijuana crosses that would be considered “duds” due to low psychoactive properties nonetheless contained high levels of CBD, which proved useful in breeding, said Jay Noller, hemp leader at Oregon State University.

Hemp plants bred in Oregon are bushier shorter, rendering them less useful for fiber, but have gained international renown for CBD content, he said. “As I meet people, they say they want to get their hands on Oregon genetics.”

Growing hemp was inspired by personal experience for Ken Iverson, whose family owns the Wooden Shoe Tulip Farm.

When his father, Ross, was dying of cancer, the extract proved successful in alleviating pain without the opioid-induced “mental fog” that inhibited communication with friends and family, Iverson said. “It turned into a much more positive process than when he was drugged and out of it.”

Since then, Iverson has jumped into the hemp market with both feet. Not only is his family growing about 200 acres of the crop this year, but they also extract CBD to sell to wholesalers and through their own retail brand, Red Barn Hemp Products.

As a new industry, it’s filled with “dreamers, schemers and a few honest people,” so finding reliable clients for CBD extract has felt precarious at times, he said.

Even so, technologies for harvest and extraction are improving while the banking industry is becoming more amenable to working with hemp companies, Iverson said.

The popularity of CBD has given rise to “a bit of a gold rush” but Iverson expects to stay in the hemp industry in the long run.

“Nobody has any idea how big the market actually is,” he said.

On the legal front, the hemp industry has stabilized as Congress has gradually lifted criminal sanctions for growing the crop — first with the 2014 Farm Bill, which permitted state-sanctioned research of the plant, and more recently with the 2018 Farm Bill, which has essentially decriminalized it at the federal level.

Though the prospect of getting thrown in federal prison for planting hemp has faded, major questions still loom about federal regulations for marketing CBD by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“It depends a lot on what the FDA will do,” Iverson said.

A key unknown is whether CBD will be treated more like a food supplement, allowing the compound to be widely sold without heavy oversight, or more like a pharmaceutical, which would subject it to close federal scrutiny.

It’s possible the agency won’t take an “either/or” approach and instead regulate CBD products on a spectrum, depending on how much of the extract they contain, said Courtney Moran, an attorney and president of the Oregon Industrial Hemp Farmers Association.

“It could be different pathways depending on concentration,” she said.

Another crucial regulatory question is the threshold at which hemp contains enough tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, to be legally treated as marijuana, its psychoactive cousin.

The standard is commonly set at 0.3 percent, but it’s unclear whether the USDA will require testing for the total level of THC or the type known as “Delta-9,” which is intoxicating.

Varieties that contain 0.3 percent or less of Delta-9 THC could test as high as 0.4 percent to 0.7 percent in total THC, said Moran.

If the USDA decides to test for total THC, hemp cultivars that are desirable to farmers could be rendered off-limits.

“That would mean a lot of the genetics being grown now would not necessarily be compliant anymore,” Moran said.

Breeders could cross-pollinate varieties to lower the total THC content of hemp, but that takes time and could have unwanted side-effects.

“They wouldn’t have the CBD percentages that we see currently,” she said.

In anticipation of the USDA’s decision, the Oregon Department of Agriculture will be requiring hemp to test below 0.3 percent in total THC beginning in 2020.

However, that rule may be changed if USDA goes in a different direction, said Summers. Until then, uncertainty about the THC limit will be another regulatory factor that makes hemp cultivation a unique challenge among Oregon crops.

“You don’t need to read the law as much to plant corn,” she said.