Small town, big emergencies

Published 5:00 am Friday, September 27, 2019

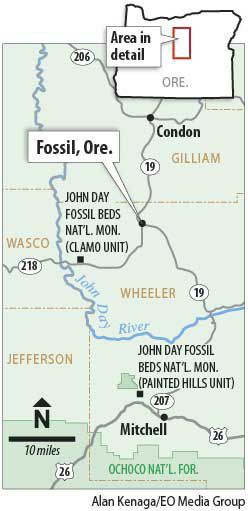

- Fossil, Ore. map

FOSSIL — It was the kind of mass trauma that sends a shudder through rural Oregon’s medical infrastructure.

On Memorial Day weekend two years ago, late at night, a woman drove her car head-on into a pack of about 45 Gypsy Joker motorcyclists who were rumbling east on the John Day Highway toward an annual rally and campout.

The driver killed three people and badly hurt half a dozen more. The whole region jumped in to help, of course, not just from Fossil, Spray and Mitchell, but also from Condon, Arlington and beyond. Volunteers mixing with sheriff’s deputies, state troopers and helicopter med-evac crews.

Amanda Roy, one of two physician assistants at Wheeler County’s only medical clinic, worked that night.

“Double amputation. Single amputation,” she said quietly. “I hope that never happens again.”

But it could, especially as Oregon grows and more motorcyclists, bicyclists, hikers, rock climbers, campers, anglers and rafters discover the stark beauty of the state’s big empty spaces. Wheeler County, where the motorcycle accident happened, also has about 200,000 tourists a year visiting the dispersed units of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument.

Wheeler County epitomizes the challenges of rural health care.

Wheeler is the least populated county in Oregon, with more square miles than humans — 1,717 to 1,450. It has no hospital and no doctors. The Asher Community Health Center in the county seat of Fossil, population 475, is where people go for medical care.

And yet, as clinic CEO Joy Andersen says, “Every emergency that happens in the city happens here, too.”

Not with the same frequency, of course, but the impact ripples.

In addition to lacking a resident doctor, the county doesn’t have a dentist or optometrist. A pair of physician assistants, Roy and Joseph Brill, handle primary care at the Asher Clinic. A doctor from Hood River oversees the P.A.’s work and visits the clinic twice a month. Two dentists, from Portland and Bend, rotate in monthly to see patients. Meanwhile, mental health screening is available by video hookup.

The clinic lacks ultrasound equipment. Mammograms are done by Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center in Boise, Idaho, 290 miles away. The hospital sent its mobile mammography unit, a 42-foot motorhome, to Fossil twice this year. The crew screened 25 patients in March and 27 in July. Previously, the women in town took an occasional bus to Bend for mammograms.

Three years ago, Casey Eye Institute of Oregon Health and Science University in Portland teamed up with the optometry program at Pacific University in Forest Grove to provide two days of eye exams in Fossil. People still talk about it.

Roy said some people hadn’t had their eyes checked in 10 to 20 years. “They found a cancer,” she said.

Ambulances are stationed in Fossil, and in Spray, population 160, and Mitchell, population 140. But the crews are all volunteers. Hit a deer out there on the highway or have a stroke out on the ranch, it might take an hour before an ambulance crew can assemble and get to you. It may take another hour or two before it delivers you to a hospital in Prineville, Madras or John Day, or links up with a helicopter to take you to Bend.

The county ambulance crews lack anyone certified beyond intermediate level in emergency medical care.

Any incident stretches the system: In early August, the Spray ambulance needed to haul a patient 32 miles to the Asher Clinic in Fossil, but some of the regular volunteers were off fighting a wildfire. A sheriff’s deputy left his patrol vehicle and jumped in to drive the ambulance while Joan Field, who works at the clinic and is the volunteer coordinator of the Spray ambulance, tended the patient.

Everyone in the county’s medical network wears multiple hats. Field’s husband, Scott, is chief of Wheeler County Fire and Rescue and is Spray’s training officer.

Susan Moore, Asher Clinic’s chief operations manager, also coordinates the volunteer ambulance team in Fossil and serves on the county’s search and rescue team.

In such a sparsely populated county, the work often turns personal. Moore said she had to leave her daughter’s bridal shower for a chest pains call. “How can you not go?” Moore asked.

And when the ambulance rolls, Moore said, “Usually it’s someone you know.”

Rural care challenges

That aspect of community medical work is among the things Robert Duehmig raises with Oregon Health & Science University students who show an interest in rural medicine.

“You’re going to see your patients at the grocery store,” he said. “How do you feel about that?”

Duehmig directs the Oregon Office of Rural Health at OHSU in Portland. Legislators and government agencies recognize the need to improve health care access in rural areas, and multiple efforts to accomplish that.

In some cases, newly minted doctors and nurses can have student loans forgiven or reduced if they agree to work in rural areas for a couple years. Pacific University, a private school in Forest Grove, Ore., developed a rural health care track for students learning to be physician assistants; Amanda Roy at the Fossil clinic is one of the graduates.

Money, personnel and medical equipment shortages are constant, but Duehmig said he is confident regarding the quality of rural health care.

But emergency ambulance service is heavily dependent on volunteers, hospice and home health care are spotty, Duehmig said, and rural areas lack easy access to specialists.

“Social determinants” such as housing, transportation, schools, jobs, age and insurance coverage complicate the infrastructure, as do rates of hypertension, diabetes, smoking and obesity.

Rural Oregonians are disproportionately older and poorer than urban residents. In Wheeler County, data from 2014-15 showed nearly 32 percent were older than 65 and about 23 percent lived at or below the poverty line. The statewide averages are 17.6 percent and 13.2 percent, respectively.

Ten Oregon counties, Wheeler among them, are classified as “frontiers,” meaning they have fewer than six people per square mile. But they aren’t all the same. It’s one thing to live 20 miles from surgeons in Eugene, quite another to live 100 miles from a specialist in Bend.

“Coastal rural and Willamette Valley rural are different than Eastern Oregon rural,” Duehmig said.

Financially, Asher Clinic in Fossil is relatively stable. It’s a non-profit, and is designated a Federally Qualified Health Center, so receives federal grant money. A health care property tax district helps subsidize service. Additional revenue comes from Medicare and private insurance reimbursements, and all patients are asked to pay on a sliding scale.

No one is turned away.

The clinic has satellite offices in Spray and Mitchell that are open two days a week.

Still, shortcomings and demands abound.

Working at an isolated rural clinic “has to make sense to you,” said Joseph Brill, the other P.A. at Asher. He ticks off some of the problems: The closest pharmacy is 20 miles away in Condon. The clinic made a special arrangement with the Post Office to get lab samples delivered in a timely manner. Vaccines travel by personal car, in a cooler.

“I can’t tell you how many people need physical therapy,” which isn’t available, Brill said. Clinic workers need training and certifications that will allow them to do more, but attending training leaves the clinic shorthanded.

“Everyone chips in and does what needs to be done,” Brill said. “You’re in it together.”

Roy, who has worked in Fossil for a bit more than seven years, lives catty-corner from the clinic and sometimes wishes she and her husband lived out a bit from town.

“Where are you going to go if you need stitches and the clinic is closed and the hospital is an hour and a half away?” Roy asked. “My porch, evidently.”

One time, a man dropped his pants on her porch to show her exactly what was troubling him.

In mid-August, a man came pounding on the clinic door at 8 p.m. on a Monday. The clinic was closed but Roy happened to be inside, catching up. The man had shot himself in the hand while putting a sheep down for butchering. He was steadying the sheep’s head when he pulled the trigger.

“Really there are no boundaries in rural medicine,” Roy said. “When you’re it, you’re always it.”

On the other hand, Roy said the wide variety of work pushes her to the edge of her training. She isn’t limited to treating sore throats and coughs, as she puts it. And with the challenging work comes “the joy of caring for a community I know really, really well,” she said.

And it’s rural Oregon, with all its charm.

In August, two cowboys burst in the clinic door carrying a girl who’d been showing her prize steer at the Wheeler County Fair next door. The girl was blowing away the judges, one of the cowboys said, until the steer stepped on her foot. Roy checked and found it wasn’t broken.

“She was able to show her pig that afternoon,” she said.