Working off the farm

Published 4:30 am Sunday, June 30, 2019

- Non-farm income/custom work

Working off the farm can have many upsides but the underlying motivation is usually simple: Making ends meet.

A reality of life in the countryside is that most agricultural operations often don’t generate enough steady revenue for a farmer to survive without holding another job.

“There are a lot of challenges that come with farming, and stability of income definitely is one of them,” said Angi Bailey, an Oregon nursery owner who also works for an agribusiness group. “There comes a point where you just can’t pay the bills.”

Of the 2 million primary producers in the U.S. — those in charge of major decisions and day-to-day management of the farm — more than 60% work at least part of the year for another employer, according to the USDA’s recently published 2017 Census of Agriculture.

About 63% of those growers devote more than 200 days a year to off-farm work, nearly full-time employment.

“It’s tough making a living just raising cows and making mortgage payments and putting kids through school,” said Matt McElligott, an Eastern Oregon rancher who also sells livestock feed across the Northwest.

Since feed dealerships are generally separated by long stretches of rural highway, McElligott is often traveling.

Though his wife and family help juggle the responsibilities, McElligott’s two jobs do clash on occasion, such as the time 100 calves got loose when he was four hours away from his home near North Powder.

Even when things are going smoothly, there’s seldom any downtime.

“It’s early mornings and late nights and taking vacation days working on the ranch,” McElligott said. “There’s sacrifices there, but that’s what I like to do, so for me it’s not a sacrifice.”

Young and old

Not surprisingly, off-farm work is most common among young farmers who’ve yet to find their financial footing: About 80% of principal producers under 35 hold other jobs.

At age 30, Dylan Wells qualifies as a young producer, but he’s no novice at farming. He’s been operating a miniature ornamental pumpkin business, Autumn Harvest, with his family for the past 15 years.

Changed circumstances in recent years — including marriage, his father’s chronic illness and new business regulations — have prompted Wells to branch out into doing home renovations and real estate.

Wells plans to stick with farming because he relishes the hustle and bustle of running the agricultural business, which is now based near Woodburn. However, he enjoys the variety of “flipping” homes, which also lets him work as his own boss.

“It’s something new every day, it’s not the same,” Wells said. “I love problem solving.”

Off-farm work isn’t solely the province of growers who are young, beginning or small-scale. Nearly one-third of producers with farms earning more than $1 million in annual revenues also work elsewhere, as do more than a third of those whose farms encompass 2,000 acres or more.

Apart from money, off-farm jobs can provide other forms of security, such as health insurance and retirement plans.

Outside experience

Some professionals who’ve devoted years to an outside career may also be reluctant to switch their focus entirely to agriculture, said Jon Paul Driver, an industry analyst with Northwest Farm Credit Services.

“They may not want to give up some of the work they’ve been doing. It brings a diversity back to agriculture as well,” he said. “There’s room for innovation for someone who’s worked in other sectors of the economy and can bring something back to the farm.”

While off-farm work is a familiar component of rural life, USDA’s statistics don’t indicate it has become more widespread. Between 2007 and 2017, the proportion of primary producers who work off-farm has actually decreased from nearly 65% to 58%.

The decline could be a facet of the rising age of U.S. primary farm producers, which crept up from 57.1 years to 59.4 years during that decade.

“Baby boomers are still a significant portion of producers, and that’s what’s driving your off-farm income discussion,” said Driver.

Some growers may have retired from their off-farm jobs while still working in agriculture, possibly driven by the particular economic fluctuations seen during that decade, he said.

The overall U.S. economy suffered a severe recession after 2007, followed by years of a lackluster employment picture, while commodity crop prices were often solid, Driver said.

“Off-farm opportunities were not as strong, which may have contributed to fewer off-farm jobs,” he said.

Despite this shift, off-farm income has remained vital to most U.S. farm operations, many of which earn negligible revenues or lose money.

Though the average net cash income per farm is $43,000, more than half of U.S. farms are unprofitable, with an average loss of $22,000.

Lifestyle matters

Lifestyle may account for part of the reason that growers are willing to work off-farm to subsidize their agricultural operations, though they’re probably motivated by more tangible reasons as well, said Carrie Litkowski, senior economist with USDA’s Economic Research Service.

The average value of agricultural land and buildings was $1.3 million per farm in 2017, up from $790,000 in 2007.

From the grower’s perspective, hanging onto increasingly valuable farmland may be worthwhile even if the operation is barely self-sustaining, said Litkowski.

“I may be breaking even, but I have this land as an asset,” she said. “They might even see that as a net gain.”

For Matt Brechwald, working as a police officer was necessary to support his livestock and hay operation near Kuna, Idaho, but the off-farm job ultimately felt too distracting.

“The things you need to be there for, a full-time job will keep you from being there for,” he said. “The con for me is I was living two different lives.”

To supplement his income, Brechwald started a side business in gopher control that eventually became successful enough for him to quit law enforcement.

As an entrepreneur, he could be flexible enough with his schedule to pivot to farm duties when necessary.

“I didn’t have to ask for time off or a vacation day and possibly be denied,” Brechwald said.

Nuanced question

Whether such agricultural businesses are considered off-farm work by USDA is a nuanced question — the census counts revenue as farm-related income unless it’s a completely separate business.

Exactly where the line is drawn depends on the perspective of the survey respondent.

“It’s counting on the farm operator to make that distinction,” said Litkowski.

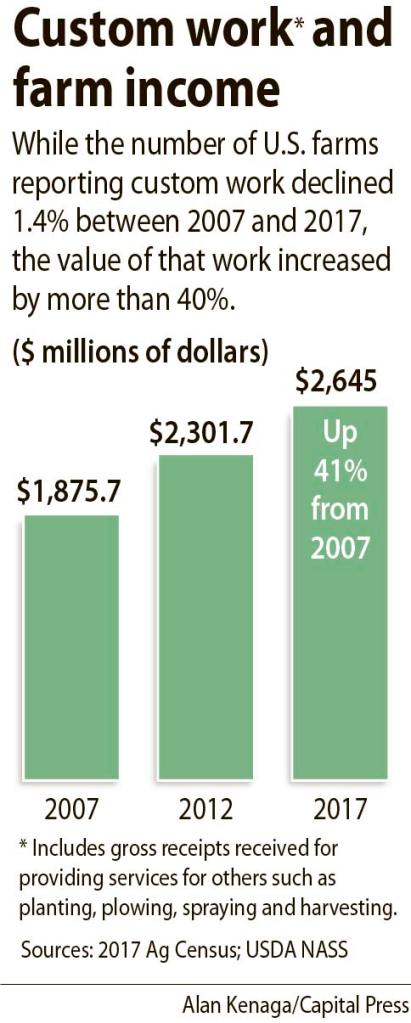

The number of farms engaging in custom work and agricultural services has dropped slightly, from about 121,900 in 2007 to 120,000 in 2017, even as their total revenues have increased in that time from $1.875 billion to $2.65 billion.

Farmers can expand into entrepreneurial ventures with assets they already own, as long as they find the right niche, Brechwald said.

“Are there people I can help with this equipment?” he said. “If you need it, that means somebody else needs it, too.”

Brechwald’s experience with off-farm income inspired him to begin an online podcast about the subject, which has earned money through advertising and has led to opportunities to produce broadcasts for agricultural companies and organizations.

Spending time in the studio continues to supplement his farm income, though it’s more than just a cash-generating enterprise.

“I enjoy doing it enough that I think I would continue doing it,” Brechwald said.

For Angi Bailey and her husband, Larry, running their nursery near Gresham, wasn’t so much the fulfillment of a lifelong dream as an unexpected development when her mother suddenly died in 2005.

“I hadn’t had my sights set on going back to the nursery,” she said. “I didn’t know where we were headed but I didn’t think it was going to be here.”

Even so, farming suited the couple and Larry left his job at a major technology company to operate the nursery full-time. Unfortunately, the nursery industry hit tough times soon after they inherited the operation, eventually forcing Larry to return to off-farm work as a patent agent for a law firm.

“He would much rather be building a greenhouse or driving a tractor,” she said. “If he could be out in the dirt every day, he would.”

Bailey herself has taken a second job as a grass roots coordinator for Oregonians for Food and Shelter, an agribusiness group that educates the public about the safe use of pesticides, fertilizers and biotechnology.

“Even off-farm, I’m still working with farmers and foresters,” she said.

The couple’s off-farm jobs are in line with those of other farmers: Nearly 36% of farm operators and their spouses held “management and professional” occupations, which is a higher percentage than any other category of work, including sales, service, natural resources or transportation, according to a USDA study.

Between the two of them, Angi and Larry Bailey share day-to-day management responsibilities at the nursery, which has been easier than expected because they both work from home some days.

“We were able to coordinate well enough that things got done and got done well,” she said.